by Dr. Ellen Chapman, Cultural Resources Specialist, and Dr. Elizabeth Horton, Cultural Resources Reviewer

For the past several years, Cultural Heritage Partners, PLLC has represented six federally recognized tribes headquartered in the Commonwealth of Virginia. Our lawyers and archaeologists have assisted these tribes with government consultation, industry engagement, and reviews of thousands of undertakings in the Commonwealth. This blog post is based on our archaeologists’ recent presentation at the Mid-Atlantic Archaeological Conference. As a companion piece, see our working recent bibliography on Virginia tribes.

Insufficient and Inaccurate Characterizations of Tribal Histories in CRM Endanger the Heritage of Virginia Tribes and Threaten Efficient Project Permitting

Cultural resource management (CRM) research is an essential part of compliance with the National Historic Preservation Act. In several contexts throughout the Commonwealth, state and local laws also require this type of research. CRM studies comprise 95-99% of the total archaeological research conducted across the country and is the field of record for most of the archaeological, architectural, and cultural landscapes resources that make up our national cultural patrimony. Many companies and people working in CRM are experts in the discipline and do excellent, thoughtful work. Unfortunately, there are also significant business challenges in CRM that create budget pressures and streamlined approaches that reuse work from previous projects. Throughout the country, reductions in site-specific background research and methods development can lead to inaccurately characterized historic and cultural resources.

In Virginia much of the CRM research — even research conducted since federal recognition of seven tribes in 2016 and 2018 — suffers from significant deficiencies that result in inaccurate characterization of tribal histories, underrepresentation of tribal historic properties, erroneous assumptions that historic sites are not tribally associated, and a lack of informed assessment of properties’ eligibility as traditional cultural places (TCPs). These limitations perpetuate Virginia’s erasure of its Tribal Nations and their ongoing contributions to Virginia history, and they obstruct the efforts of Tribal Nations to identify and protect their important cultural places. Moreover, when CRM reports demonstrate insufficient understanding of significant tribal sites, tribes are likely to demand additional engagement with federal permitting agencies, causing delays for project proponents.

CRM Reports Fail to Recognize Tribal History and to Identify Tribal Historic Properties

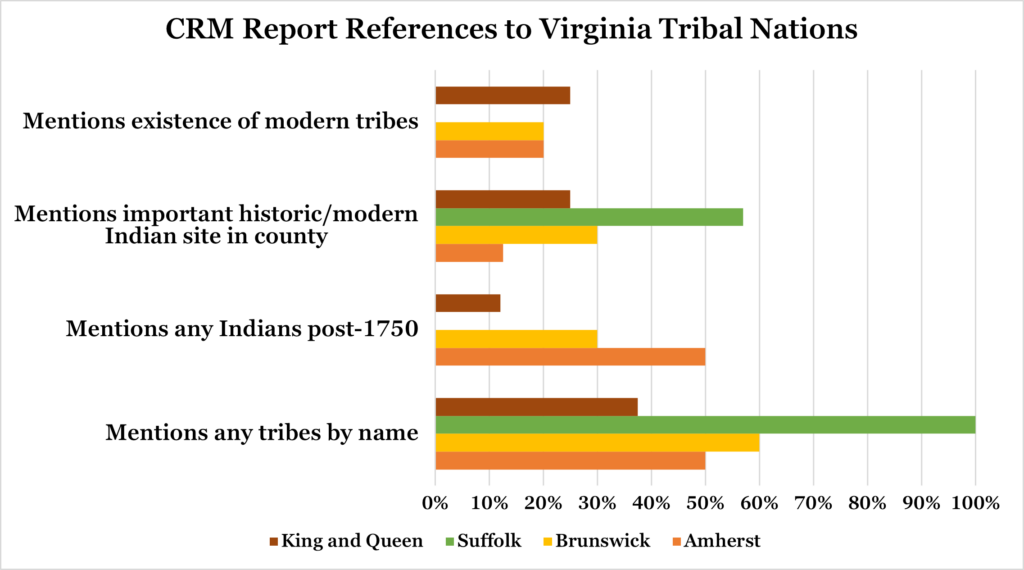

To examine this issue systematically, we reviewed 35 post-2010 archaeological reports for sites in Amherst, Brunswick, King and Queen, and Suffolk Counties.[1] We selected these counties because all include sites of historic and contemporary importance for tribes in Virginia:

- Amherst is the site of the Monacan Tribal Center and modern tribal facilities. In addition, the Bear Mountain Indian Mission School and the St Paul’s Bear Mountain Episcopal Church are both National Register-listed 19th century historic architectural sites associated with the Monacan people.

- Brunswick is the location of Fort Christanna, a National Register-listed 18th century archaeological fort established by Governor Spotswood to missionize Virginia Indians, forcibly westernize them through education, and to enlist tributary tribes to provide Indian military defenses during the Tuscarora War.

- King and Queen County is the location of the modern Rappahannock Tribal Center, the Rappahannock Tribe’s second reservation, and the National Register-listed Chief Otho S. and Susie P. Nelson House associated with the Rappahannock Tribe’s 20th century history.

- Suffolk is the site of a 19th century Nansemond settlement, the 17th century sites of Nansemund and Dumpling Island, and the modern Nansemond Tribal headquarters at Mattanock Town.

We found alarming results when we reviewed the bibliography and background literature sections of reports, along with the assessments of previously recorded sites in the region. Of the 35 reports, which had an average publication date of 2017:

- Only 62% reference any named tribe from any time period;

- Only 23% mention any tribes or individual native people post-1750;

- Only 30% reference the historical or contemporary tribal centers located in the county (and many that do only mention the 17th century village sites); and

- Only 16% mention the existence of modern tribes.

Unfortunately, these omissions are consistent with a broader failure to recognize tribal historic resources and acknowledge the persistent tribal presence in Virginia. Some additional shortcomings that we often see in CRM reports for projects in Virginia include:

- Failure to discuss documented historic tribal architectural resources or raise the possibility of finding tribal architectural resources, such as buildings or cemeteries, even when these places are labelled on maps or are historic properties within the search area.

- Failure to mention historic tribal reservations located within or near report study areas.

- Only sparse references to local tribal history and participation in post-1700 historical events (such as tribes’ ongoing habitation in the area, visits to Virginia tribes by anthropologists in the 19th and 20th centuries, or Pamunkey participation during the Civil war as guides for the Union Army).

- Failure to explain National Register eligibility decisions or reference specific site or building conditions.

- Failure to consider the potential for identification of tribal traditional cultural properties– even when the report includes areas where researchers have previously identified tribal traditional cultural properties or landscapes.

- Persistently using boilerplate language that excludes recent archaeological and architectural scholarship and denies the reality of the historic and modern presence of Indigenous peoples of Virginia.

This Failure to Acknowledge Tribes Causes Significant Business Risks to CRM Companies and Project Proponents and Disrespects Tribes

For project proponents, failure of their cultural resources consultants to identify and evaluate historic properties appropriately creates business risks, such as tribal opposition to permits, disagreements with federal agencies and state historic preservation offices that lead to the need to repeat or augment work already completed, and the greater likelihood for an unanticipated discovery after a permit is granted, all of which can lead to significant delays. In our firm’s experience, the most egregious errors and misrepresentations of cultural resources by CRM consultants have led to multi-year delays and seven figure financial settlements with tribes.

For tribes, the failure of CRM companies to acknowledge their existence and their cultural heritage contributes to the ongoing erasure of modern native people and communities, perpetuates the absence of native sites and historic settlements in the historical record, and hinders the identification and evaluation of traditional cultural properties, which are routinely recorded by compliance-related CRM in other regions (for some recent examples, see hydroelectric dam relicensing projects in Vermont, New Hampshire, and Massachusetts, or TCP concerns on the Line 5 pipeline in Michigan).

These failures also create a missed opportunity for tribal-CRM partnerships. Cultural heritage grant opportunities are more accessible than ever for both federally and state recognized tribes, and recent environmental justice and climate change legislation have created new opportunities for heritage funding. CRM companies have important expertise that tribes often need as they steward land holdings, construct developments in tribal communities, and evaluate their historic preservation priorities. Yet the lack of relationship between most CRM companies and tribes in Virginia limits collaborations that are sorely needed to identify and evaluate tribal resources.

Recommendations for CRM Companies

Here are our top six recommendations for CRM companies looking to improve their processes for projects that are planned in Virginia:

- Familiarize yourself with the ancestral interest areas of state and federally recognized tribes and any historical resources the tribes themselves may have made available.

- Develop a checklist for areas of highest tribal significance to:

a. assess whether to recommend ethnographic study to evaluate for TCPs;

b. determine whether a historic architectural property might have a tribal association (such as through geographic lists of tribal last names); and

c. coordinate with local tribes to determine whether they might have information necessary to make a complete determination of eligibility for the National Register. - Update background literature language and boilerplate to include additional context from more recent sources that reflect greater collaborative research with tribal communities (see our bibliography to get started).

- Create internal policies regarding how information about tribes and descendant communities is reviewed and included in reports.

- Develop an awareness of situations where early tribal consultation by the federal or state agency, the project proponent, or subcontractors like your CRM company might provide insights into tribal concerns and important input into project design and methods. Too often, tribal consultation does not begin until years after your report was submitted to the client. When tribes are not consulted regarding survey approaches in their traditional areas, projects can be hung up in delays and requests for additional work.

- Seek tribal partners to conduct work that is meaningful and pushes the discipline and the industry forward. Tribes are eligible for federal funding to support projects they can perform in collaboration with CRM companies such as coastal resilience and adaptation, tribal heritage grants, National Endowment for the Humanities grants, and in Virginia, BIPOC grants offered through the Department of Historic Resources.

While seven tribes in Virginia only recently received federal recognition, state and federally recognized tribes with ancestral interests in Virginia have been actively engaged in historic research for decades. It’s long past time that CRM reports stop perpetuating myths that tribes left Virginia and never came back, that they all died out, or that tribes assimilated to the point of having no modern tribal identity. With greater outreach and collaboration, tribes and CRM companies could productively explore a number of interesting projects together. Examples include research on the locations and extents of various historic tribal reservations, tribal 18th and 19th century movements and settlements, and the histories of 19th century tribal institutions. CRM companies could also be important partners in developing needed tools and infrastructure for tribes to manage cultural resources on their own lands. Some such collaborations have already been fruitful, such as WMCAR’s survey of coastal resources on the Pamunkey Indian Reservation and the work of the Kenah Consulting (a tribally-owned consulting firm) and the Fairfield Foundation in collaborating with tribal partners on the Master Plan for the new Werowocomoco National Park Service site.

Academic collaborations by researchers at the College of William and Mary and St. Mary’s College are also useful models for larger TCP studies, such as the Indigenous Cultural Landscape surveys on the Rappahannock, York, and Mattaponi Rivers, and the three tribal resources reports on resources associated with the Mattaponi, Sappony, and Nottoway tribes prepared in collaboration with tribes by the William & Mary American Indian Resource Center and the Department of Anthropology. With greater collaboration between CRM and tribal partners, cultural resources management consultants can dedicate their skills to some of the most exciting and fruitful areas of research into Virginia’s cultural patrimony, while providing greater public relations potential and lower reputational and logistical risk to their clients.

Conclusion

The cultural resources record must reflect accurate information: that tribes are still here, that tribes are the experts in their traditional cultural places, and that Virginia contains National Register eligible tribal resources from all eras of Virginia history, not just the Contact Era and earlier. The current state of affairs poorly serves CRM companies, tribes, project proponents, and agencies alike. We encourage all participants in CRM to pursue productive ways forward to ensure that tribal resources are recorded thoroughly and accurately.

Questions, reflections, and recommendations on this blog and the bibliography can be emailed to Ellen Chapman.

—————————

[1] We included most of the complete reports in our analysis, excluding some limited assessments. While we noted whether reports were a Phase I or Phase II and whether they were conducted for agencies that only require limited background review (for example, background research requirements for archaeological work done for the Virginia Department of Transportation is limited under a Programmatic Agreement), we did not notice a huge difference between these categories.

Title image shows the Amherst County Episcopal Mission to the Monacan Indians as illustrated on the 1935 Amherst USGS map.